December 25, 2024

Denver transformed into a snow globe on Christmas Eve, 1982. The blizzard blanketed the city under a thick, relentless snowfall that muffled the world into stillness. Streets vanished beneath drifts that grew taller by the hour, and cars became shapeless lumps of white, their outlines fading into the storm’s chaos.

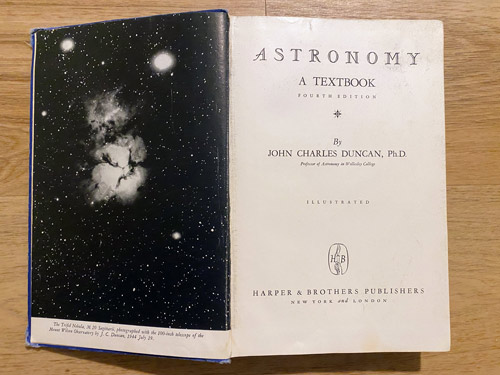

I wandered from room to room, watching the snow cover the windows, then stopped in front of my dad’s bookshelves. I scanned the titles from shelf to shelf. One tattered book without a spine immediately caught my attention. I took it down; its faded blue cover displayed an illustration of the Orion constellation engraved on the front.

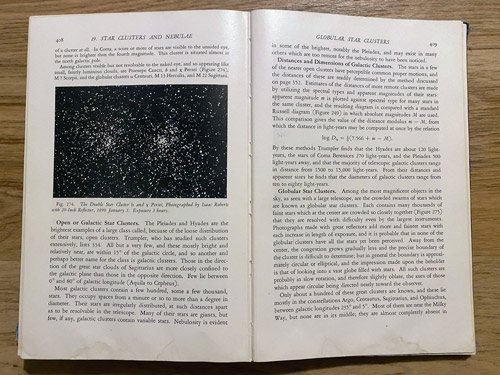

Flipping through the coffee-stained pages, I discovered black-and-white images of celestial objects interspersed among the academic text. Star clusters, galaxies, and ethereal nebulae captured by renowned observatories floated off the pages. I first grasped the universe’s vastness and inherent beauty in those brief moments.

Later that evening, I lay beneath the branches of our Christmas tree, gazing up at the colored lights with my astronomy book in hand. No rumble of airplanes from nearby Stapleton Airport shook the house, and no one dared to traverse the snow-covered roads by car. It was a night with the minutes and hours frozen in winter air; just me, a Christmas tree, and a collection of photographs from the heavens.

Forty-two years have passed since that blizzard day in Colorado. Since then, I’ve learned that a busy life, measured out by coffee spoons, has ways of stealing away the magnificence surrounding us. I yearn more for the quiet moments, the tender conversation, the silent prayers.

I suspect that’s why I love astronomy. Amateur astronomy lets me journey countless miles with just a few steps out the back door. Nights out under the firmament bring moments of respite and have a way of getting me back to Christmas Eve in 1982.

Since those days, I’ve worked my way through Duncan’s astronomy book, eager to see or photograph those captivating objects I first saw in those black-and-white photos. What strikes me all these years later is that I never thought to ask my father why he owned the astronomy book. We never had those conversations, and he’s been gone for a long time. I didn’t have a mentor in this wonderful hobby many of us treasure, but it all began with this book—a genuine passport to the stars!

This Christmas, I reflect on the notable observations that have taken my breath away over the years.

- Seeing Saturn for the first time

- Using my small department store telescope, trying to find Halley’s Comet

- Sitting in the snow, freezing my toes off, and finding my first star cluster, M41

- Seeing Hale-Bopp, my first naked-eye comet, grace the skies.

- Finding Uranus for the first time—I never thought as a kid I would see the distant planets

- Taking an iPhone photo of the Milky Way from the Florida Keys

- Capturing the Great Whirlpool

- Finding the Sombrero Galaxy, as it was one of the first black-and-white photos I saw and read about

- Seeing M57 (Ring Nebula) for the first time with my wife after purchasing a large Meade reflector telescope that filled the front room of our first apartment.

- Finding Mercury outside my bedroom window

- Feeling blown away seeing the famous double cluster

I have many favorites on this website, but these are the ones that made me pause and express gratitude for the rewarding learning journey they provided. Every now and then, I review the site’s readership statistics. It makes me happy to see so many people around the world using it as a resource, and perhaps it will become someone else’s passport to the night skies as they wait out the next blizzard or cloudy night. May they take those next steps out the back door — and let the adventure begin.

Banner photo credit: Michael Sol

One thought on “How a Denver Blizzard Inspired My Stargazing Journey”