March 20, 1997

A pivotal chapter in my astronomy journey began during the Denver Christmas Eve Blizzard of 1982. Nearly fifteen years later, another unforgettable moment unfolded on an unusually warm March night in Colorado Springs, when I seized the perfect clear‑sky conditions to view Comet Hale‑Bopp.

Many memories fade over time, but I still recall that evening as twilight deepened. On the western horizon, a subtle shimmer, almost imperceptible at first, brightened into a soft glow just above the treetops.

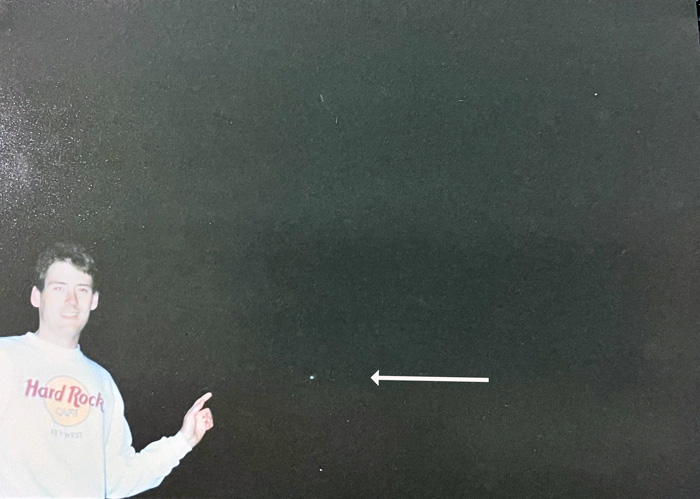

“There it is!” I exclaimed, pointing out the silver smudge to my wife.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have a telescope at the time—only a pair of binoculars and a 35 mm film camera. That night, the comet shone at approximately magnitude -1, making it visible even from suburban areas with significant light pollution. By comparison, Sirius, the brightest star in the night sky, glows at magnitude -1.4, only slightly brighter than Hale‑Bopp.

My wife and I quickly set up our tripod. I mounted the camera, screwed in the shutter‑release cable, and began taking exposures of varying lengths, unaware of exactly what I was capturing without today’s digital previews. I must have gone through several rolls of film!

Then, inspired by the comet’s unexpected brightness, we tried a simple trick: firing a flash to illuminate me pointing at the comet, then leaving the shutter open long enough to register Hale‑Bopp’s tail.

Hours earlier, children had been playing soccer in the park, and families strolled along the paths. But now the park was silent with just the two of us, eyes lifted toward one of history’s most spectacular comets. This spark of wonder was ours alone until the comet dipped below the mountains and we walked back to our apartment.

When I launched this site in 2020 and returned to astronomy, I assumed I’d never see another great comet. My “once‑in‑a‑lifetime” moment felt firmly rooted in 1997—until news of a new icy visitor broke in late March 2020. Sure enough, Comet NEOWISE became a naked‑eye spectacle that summer. With my newer camera and telescope, I soon found myself tracking Comets NEOWISE, ATLAS, Tsuchinshan-ATLAS, and Comet ZTF.

I often think back to that night under Hale‑Bopp’s tail. The comet won’t return until around 4385 AD—long after I’m gone. Its voyage reminds us that life, too, is a journey punctuated by fleeting encounters that change us forever. We meet people, seize opportunities, and carry their impact forward on our own paths.

About Comet Hale-Bopp

Comet Hale–Bopp, officially designated C/1995 O1, was independently discovered by Alan Hale and Thomas Bopp on July 23, 1995. This long-period comet was exceptionally active, developing an enormous coma. Some estimates suggest its diameter was over 100,000 kilometers, which was visible to the naked eye well before its closest approach to the Sun.

As it traveled inward through the inner Solar System, the comet displayed two distinct tails: a bright, dust-laden tail that curved gracefully behind the nucleus and a fainter, straight ion tail streaming directly away from the Sun due to the influence of the solar wind. Its unprecedented brightness lasted 18 months from discovery until it faded, making Hale–Bopp one of the most widely observed and photographed comets of the 20th century.

At perihelion on March 22, 1997, Hale–Bopp passed within 1.315 astronomical units of the Sun, bathing its icy nucleus in intense solar radiation and driving spectacular increases in activity. Skywatchers around the globe were treated to a celestial show: under dark skies, the comet reached a peak apparent magnitude of around –1, rivaling even the stars of the Big Dipper in brilliance. Scientific teams deployed across multiple continents to study its composition, detecting complex organic molecules such as formaldehyde and ethane, and gleaning insights into the primordial matter of the early Solar System.

Though Hale–Bopp will not return for over 2,500 years, its dramatic appearance in 1997 left an indelible mark on both professional astronomy and public imagination.