July 20, 2025

For most of human history, the stars were mysterious pinholes of light in the night sky. Then came the telescope, a revolutionary invention that not only enhanced our vision but also redefined our place in the universe. Before the advent of the great observatories we have today, these remarkable machines made of metal, glass, and ingenuity opened up the heavens for exploration. Here’s my personal Top 10!

1. Galileo’s Refractor (1609)

The Spyglass That Shook the Universe

Credit: Sailko | Creative Commons

Location: Italy

Type: Refractor (30x magnification)

Claim to Fame: First telescope used for serious astronomical observation

In the summer of 1609, a man in Venice stood on a rooftop, holding a strange, slender tube of wood and glass. He aimed it at the Moon, and the world would never see the skies the same way again. That man was Galileo Galilei, and the instrument he held was the first telescope ever turned seriously toward the stars. It was small. It was crude. But it rewrote the story of the universe.

What He Saw

The Moon was his first target. But it didn’t look like the serene, flawless orb described by philosophers. Through Galileo’s refractor, it was scarred and rugged. He saw shadows creeping across craters, jagged mountains, proof that the Moon was a world, not a perfect heavenly sphere.

Public Domain

Next, he looked at Jupiter. Night after night, he observed tiny stars nearby that moved. Eventually, he realized they were moons—four of them, orbiting the planet in a cosmic dance. Today, we call them the Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Then came Venus. Galileo observed its phases, similar to the Moon’s. That made no sense in the Earth-centered model. But in Copernicus’s heliocentric system—where planets orbit the Sun—it made perfect sense. Galileo didn’t just see stars. He saw the evidence that Earth was not the center of the universe.

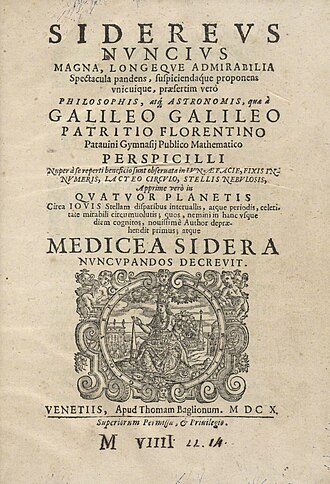

The Starry Messenger

In 1610, Galileo published Sidereus Nuncius, also known as “The Starry Messenger,” a short book that had a profound impact. It detailed his observations of the Moon, Jupiter’s moons, and the Milky Way, which through his telescope wasn’t a foggy band but millions of individual stars. You can view Galileo’s sketches and writings in an online copy of Sidereus Nuncius, posted on the Smithsonian Libraries website.

Credit: *IC6.G1333.610s, Houghton Library, Harvard University

Legacy

Every telescope today, from backyard Dobsonians to the James Webb Space Telescope, traces its roots to that summer evening in 1609. Galileo’s refractor was not just a prototype for a tool, but for a new way of thinking.

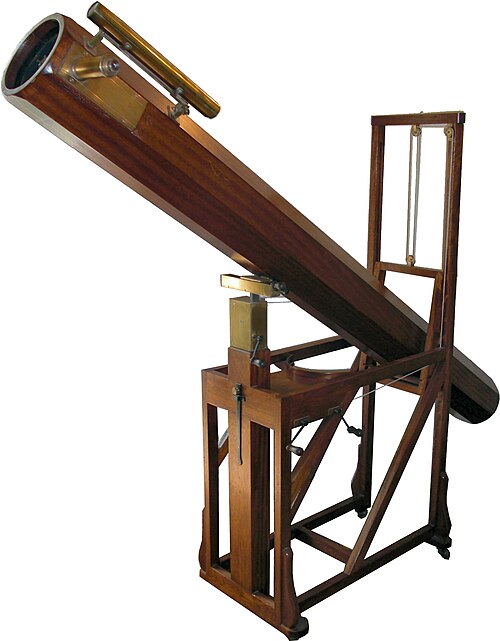

2. Newton’s Reflector (1668)

An Invention that Changed Astronomy

Location: Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire, England

Type: Reflector (1.3-inch mirror) and 6 inches in length

Claim to Fame: The first successful working model of a reflector

As the Great Plague of London raged in 1665, Sir Isaac Newton retreated to the quiet of his family home in Lincolnshire. This period of intense isolation became his annus mirabilis, or “year of wonders,” during which his genius flourished. He laid the groundwork for modern calculus, unraveled the secrets of light and color, and began to formulate his laws of gravity and motion. Amidst this whirlwind of discovery, Newton designed a revolutionary instrument to observe the heavens. In 1668, he built his first reflecting telescope.

Why It Mattered

Newton’s telescope was deceptively simple. At only six inches long, it was powerful enough to clearly display Jupiter’s moons and the crescent phase of Venus. Its revolutionary design used a mirror instead of glass lenses to gather and focus light, forever changing how we view the universe. This wasn’t just a technical trick; it represented a significant advance in astronomy, offering sharper images, greater scalability, and easier construction compared to traditional refractors.

Legacy

In the end, Newton’s reflecting telescope did more than change technology; it changed our perspective. That small, handheld device was the first step on a journey that has stretched across centuries, leading to colossal mountaintop observatories and sophisticated eyes in orbit. It remains one of history’s most powerful reminders of how a single new way of seeing can forever alter our understanding of our place in the cosmos.

3. Herschel’s 7-Foot Telescope (1779)

Backyard Telescope Changes the Solar System

Location: Bath, England

Type: Reflector (6.2-inch mirror)

Claim to Fame: Homemade telescope finds Uranus

In 1781, a musician-turned-astronomer named William Herschel pointed a homemade telescope at the night sky from his backyard garden in Bath, England, and found a new planet. That telescope wasn’t some elaborate observatory-grade instrument. It was a hand-built reflector, crafted by Herschel himself in his workshop, and it ultimately rewrote our map of the solar system.

Not Just a Hobbyist

William Herschel wasn’t a trained scientist. He was a professional organist and composer with a passion for astronomy. But he didn’t stop at stargazing. Herschel and his sister Caroline, his lifelong collaborator, built dozens of telescopes from scratch. They ground and polished their own mirrors, experimented with different focal lengths, and pushed their tools far beyond what most amateurs could achieve.

By 1774, Herschel had set up a small observatory in his garden on New King Street. From there, he began sweeping the sky systematically with a telescope he had built himself—a 7-foot-long Newtonian reflector with a 6.2-inch aperture. Compared to other scopes of the time, it was remarkably powerful and had a wide field of view, ideal for his methodical sky surveys.

The Night of Discovery

On March 13, 1781, Herschel spotted an object that looked different from the usual stars. Unlike stars, it appeared to have a disk, and more importantly, it moved. At first, Herschel thought he had found a comet.

“I compared it to H Geminorum and the small star in the quartile between Auriga and Gemini, and finding it so much larger than either of them, suspected it to be a comet.” — from Scientific Papers, vol. 1, p. 30, describing his first sighting of what would turn out to be Uranus

But over the next several nights, as he tracked its motion across the sky, it became clear: this was not a comet. It was a planet. The first new planet discovered since ancient times.

Reading about William Herschel’s discovery of Uranus always hits a nerve—it takes me right back to that night under the stars when I first spotted the planet through my own telescope. There was something surreal about it, like brushing against history. In my own small way, standing there in the quiet darkness, I felt connected to that same sense of wonder, staring at the same distant object he had once done, more than two centuries ago.

The Telescope Behind It

The telescope Herschel used that night had a speculum metal mirror—an alloy of copper and tin polished to a reflective shine. It wasn’t perfect. The metal tarnished quickly, and the image quality degraded over time. But Herschel’s craftsmanship and observational discipline made up for those flaws.

His homemade mount enabled him to sweep systematically along lines of celestial latitude, and his custom eyepieces provided sufficient magnification to spot the unusual disk shape of Uranus. It was enough to catch what no one else had noticed. Herschel’s backyard discovery rocked the scientific world. The Royal Society awarded him the Copley Medal. King George III gave him a pension and appointed him “The King’s Astronomer.” And astronomers everywhere began pushing for better telescopes and deeper sky surveys.

Legacy

Herschel would go on to build larger and more powerful telescopes, including a 40-foot monster with a 48-inch mirror that is next on my list below. But it was his modest backyard scope that made history. The discovery of Uranus wasn’t just a milestone for astronomy; it was a wake-up call that showed amateurs with drive and homemade tools could make significant contributions to science.

In an era when most believed the solar system had been fully charted, Herschel’s humble garden telescope showed there was more out there and more to come.

4. Herschel’s 40-Foot Telescope (1789)

The Giant That Reached for the Stars

Location: Slough, England

Type: Reflector (48-inch mirror)

Claim to Fame: Largest telescope in the world for 50 years

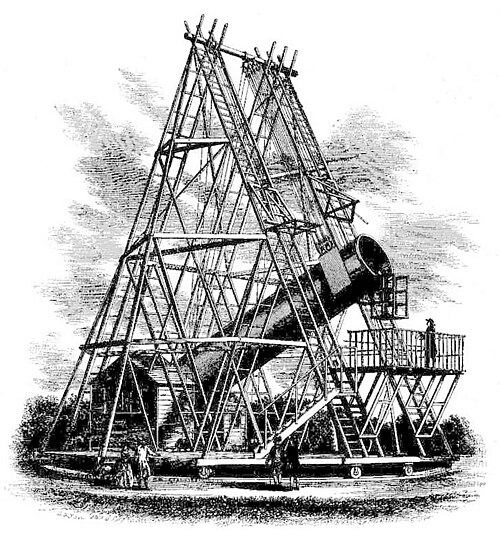

In the quiet English town of Slough during the late 1700s, a musician-turned-astronomer was constructing something unprecedented—a telescope so massive and ambitious that it dwarfed every scientific instrument of its time. This wasn’t just a tool for observing stars; it was a bold statement: the universe is larger than we realize, and we are going to prove it.

This was William Herschel’s 40-foot telescope, completed in 1789. For more than 50 years, it was the largest telescope on Earth, and it cracked open deep space like never before.

The Monster is Built

Construction began in 1785. Herschel wasn’t aiming for elegance; he wanted raw, unprecedented power. His design was a reflecting telescope with a 48-inch (4 feet) diameter mirror and a 40-foot-long tube. The entire setup weighed tons and needed a system of pulleys and scaffolding to move. It looked like something out of a shipyard: a wooden framework, a massive tube hanging vertically between tall supporting towers, and a team of assistants to operate it.

“…not a screw‑bolt in the whole apparatus but what was fixed under the immediate eye of my brother. I have seen him lying stretched many an hour in the burning sun, across the top beam, whilst the iron‑work for the various motions [of the great telescope] was being fixed.” — from Caroline Herschel’s diary, reflectively quoted in The Story of the Herschels

In 1789, after years of labor, the 40-foot telescope saw first light. On its very first night, it captured Saturn’s sixth moon, Enceladus. A few weeks later, it spotted Mimas, another of Saturn’s moons.

A New Vision of the Cosmos

Using the 40-foot telescope, Herschel conducted an in-depth survey of the sky. He didn’t merely catalog stars; he aimed to map the structure of the Milky Way itself. Most importantly, Herschel began to develop the idea that the Milky Way was just one of many possible star systems. His 40-foot telescope not only extended his view into the distance but also expanded his perspective on the universe as a whole.

The Telescope’s Fate

Despite its power, the 40-foot telescope was challenging to use. Its massive size made it hard to reposition, and England’s damp, cloudy weather didn’t help. Over time, smaller, more practical telescopes became more useful for daily observation.

Still, Herschel’s giant remained standing for decades as a symbol of scientific ambition. Eventually, it was dismantled in the mid-1800s. Only the mirror and some original pieces survive.

Legacy

Herschel’s 40-foot telescope marked a turning point in astronomy. It was the first instrument designed not just to see planets and moons, but to look deep into space. It helped shift the focus of astronomy from our solar system to the wider universe.

5. The 9.6-Inch Fraunhofer Refractor (1829)

Playing a Starring Role in Astronomy

Location: Potsdam, Germany

Type: 9.6-inch Refractor

Claim to Fame: Observed Neptune for the first time

In the early 19th century, when telescopes were becoming precision instruments rather than optical curiosities, one instrument in particular stood at the intersection of art, science, and history: the 9.6-inch Fraunhofer refractor at the Berlin Observatory. Though modest in size by today’s standards, this telescope was revolutionary, setting the standard for astronomical observation in its time and playing a starring role in one of the greatest discoveries in astronomy.

A Masterpiece of Craftsmanship

The telescope was constructed by Joseph von Fraunhofer, a German optical pioneer whose contributions to diffraction and spectroscopy continue to be celebrated in the field of science. Fraunhofer had already gained recognition for his earlier 6.2-inch (16 cm) refractor in Munich. Still, the instrument completed in Berlin in 1829 was larger, more advanced, and represented the pinnacle of lens-making craftsmanship at that time.

With a 9.6-inch (24.4 cm) aperture and nearly 15 feet of focal length, this achromatic refractor was one of the largest of its kind in the world. Its large size and sharp optics allowed astronomers to push the boundaries of what could be seen from Earth.

A Telescope that Discovered a Planet—Almost

The Fraunhofer refractor’s place in astronomical lore was secured on the night of September 23, 1846, when Johann Gottfried Galle, working at the Berlin Observatory, used it to make one of the most significant discoveries of the 19th century: the planet Neptune.

But there’s a fascinating twist. Galle didn’t stumble upon Neptune by accident. He was guided by the mathematics of a young Frenchman, Urbain Le Verrier, who predicted that the irregular orbit of Uranus could be explained by the gravitational pull of an unknown planet. Le Verrier sent Galle a letter outlining the predicted location of the new world.

Within just one hour of scanning the region Le Verrier described, Galle and his assistant, Heinrich d’Arrest, located a faint star that appeared to be moving. Night after night, it moved in a way no star would. It was, in fact, Neptune.

“Sir,—The Planet [Neptune] whose position you marked out actually exists. On the day on which your letter reached me, I found a star of the eighth magnitude, which was not recorded in the excellent map designed by Dr. Bremiker … The observation of the succeeding day showed it to be the Planet of which we were in quest.” — from Johann Gottfried Galle, letter dated September 25, 1846

Thanks to the Fraunhofer refractor’s clarity and power, Neptune became the first planet discovered through mathematics rather than direct observation—a moment that marked a fusion of theory and instrument that defined the future of astronomy.

Reading Johann Gottfried Galle’s account of spotting Neptune for the first time makes me sentimental. It brings back the memory of the night I first saw Neptune through my own telescope. Knowing he was guided by nothing but calculations and hope, and then actually found it, gives that moment so much weight. When I saw Neptune’s faint glow for myself, it wasn’t just a distant planet. It was a quiet connection across time, a shared moment of discovery between me and someone who turned math into a new world.

Legacy in Glass and Iron

Though newer instruments have long since surpassed it in size and capability, the 9.6-inch Fraunhofer refractor remains an icon. It’s preserved as part of scientific history, not just for its craftsmanship, but for its role in expanding the known boundaries of the solar system.

It reminds us that progress in science often rests on the shoulders of patient observation, careful calculation, and inspired collaboration. The telescope itself may be silent today, but it once gave voice to the outermost reaches of the known solar system.

And for that, the Fraunhofer refractor will always have a place among the stars.

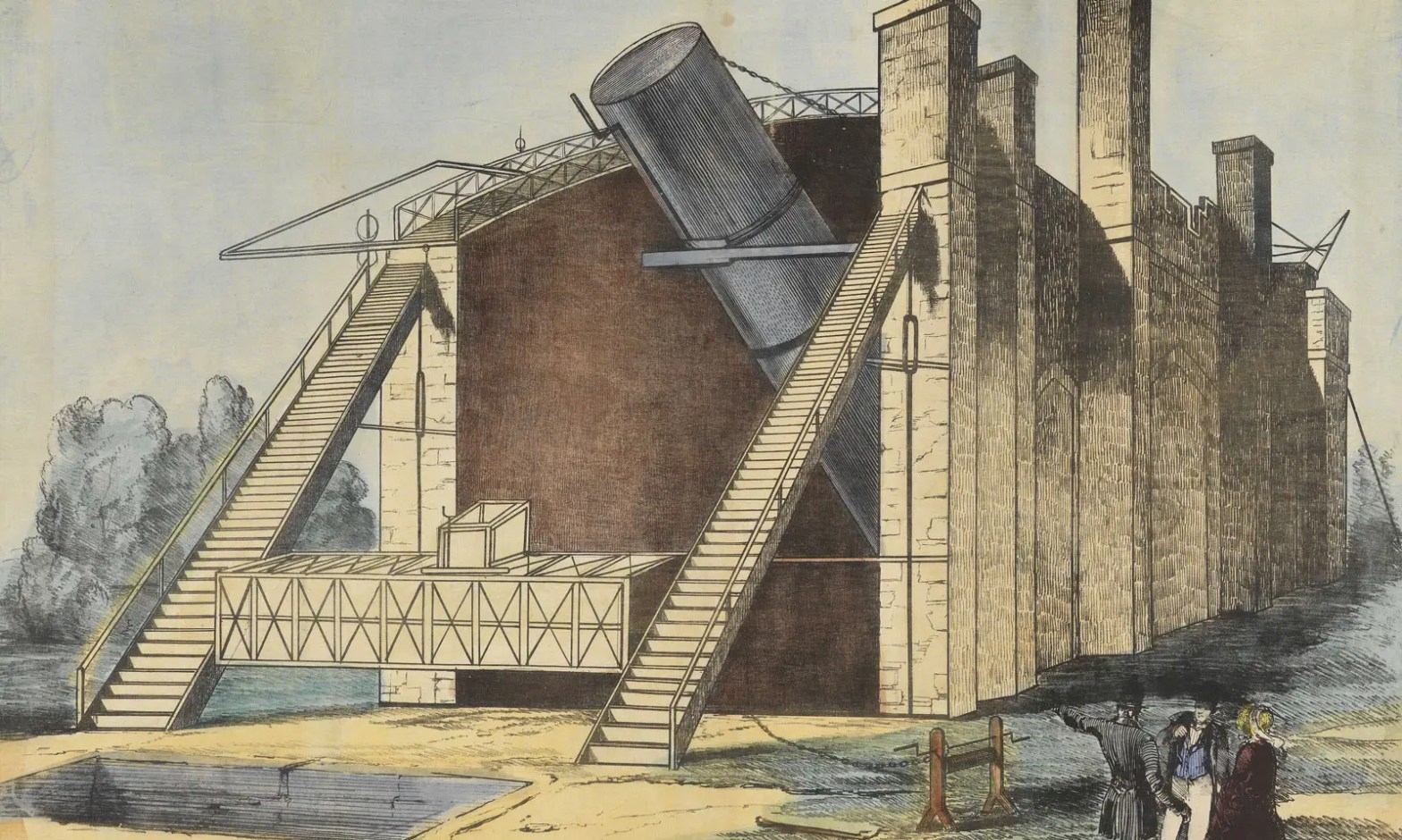

6. The Leviathan of Parsonstown (1845)

Looking Into the Universe’s Soul

Location: Birr, Ireland

Type: Reflector (72-inch mirror)

Claim to Fame: Largest telescope in the world for over 70 years

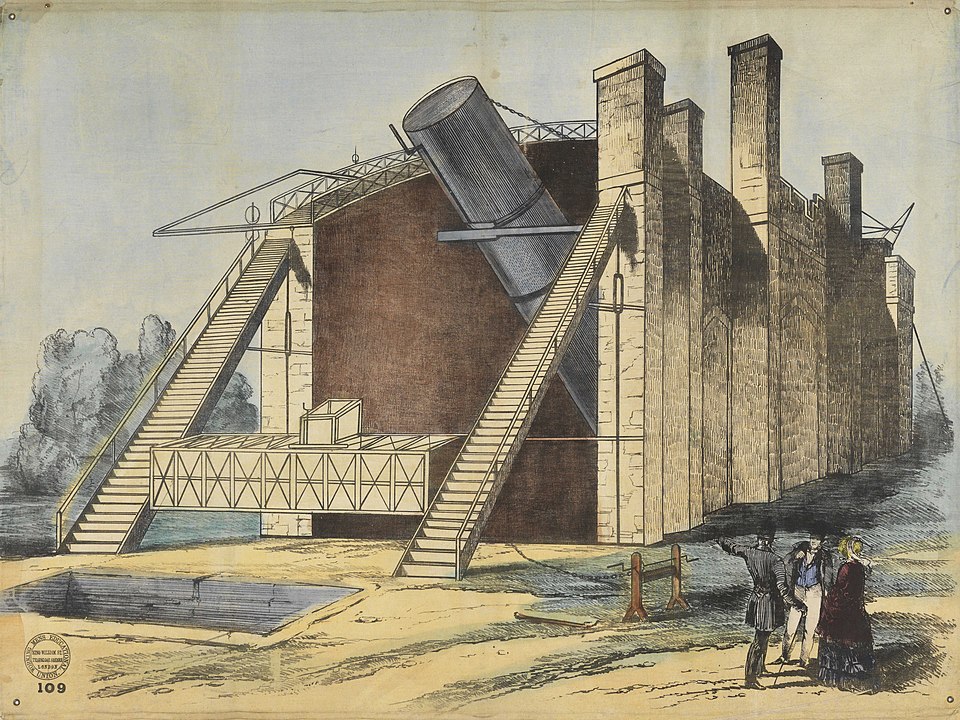

In the heart of 19th-century Ireland, a nobleman with a passion for astronomy undertook a project that seemed more fantastical than scientific. He wasn’t building a cathedral or a war machine. He was building a telescope so large that it would take teams of workers, towering walls, and tons of metal to complete.

This was the Leviathan of Parsonstown, finished in 1845, and for more than 70 years, it held the title of the world’s largest telescope. It didn’t just magnify the stars. It transformed how we understood them.

The Man Behind the Monster

The Leviathan was the brainchild of William Parsons, the 3rd Earl of Rosse. He wasn’t a professional astronomer, but he had wealth, engineering genius, and unrelenting curiosity. From his estate in Parsonstown (now Birr, Ireland), he set out to build a telescope that would go beyond what any human had seen.

Parsons wasn’t merely trying to enhance earlier designs; he was redefining the concept of a telescope altogether. His goal was to observe the mysterious, faint “nebulae” scattered across the night sky. While some scientists believed these phenomena were merely clouds of gas, Parsons had a different perspective.

Building the Leviathan

This was no backyard project. The Leviathan had a 6-foot (72-inch) wide metal mirror, weighing over 4 tons, mounted inside a 54-foot-long tube. It was suspended between two massive stone walls, like a siege engine aimed at the stars.

Just casting the mirror was a feat. Parsons experimented with a blend of molten copper and tin to create a giant, gleaming speculum metal disc. It took repeated attempts before the mirror was usable—and even then, it had to be polished by hand.

“Whatever met the eye was on a gigantic scale: telescopic tubes, through which the tallest man could walk upright; telescopic mirrors whose weights are estimated not by pounds but by tons, polished by steam power with almost inconceivable ease and rapidity, and with a certainty, accuracy and delicacy exceeding the most perfect production of the most perfect manipulation; structures of solid masonry for the support of the telescope and its machinery more lofty and massive than those of a Norman keep….” — from Telescope by Robert Smith – University of Alberta.

The telescope couldn’t pivot side to side. It was fixed between its walls and could only be angled up or down. But with teamwork and clever engineering, it worked. In a cold, foggy corner of Ireland, the Leviathan came to life.

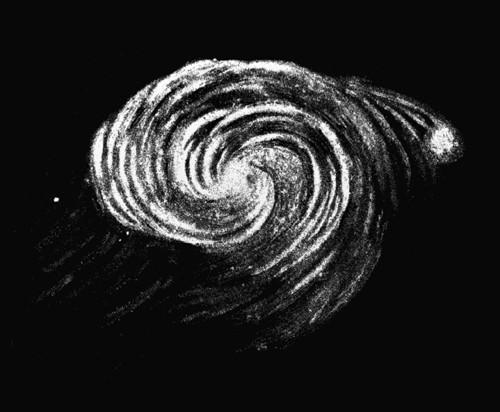

What It Saw

The Leviathan didn’t just see more—it saw deeper. With it, Lord Rosse observed and sketched countless nebulae. But the most significant came in 1845, when he turned it toward a fuzzy object in the constellation Canes Venatici.

Through the Leviathan, that fuzzy object—M51, now known as the Whirlpool Galaxy—revealed a spiral structure. It wasn’t a cloud. It was a vast, swirling collection of stars. A system in its own right.

As I reflect on Lord Rosse, I think of my own observations of Messier 51, which have been meaningful to me.

Parsons wasn’t looking at a simple gas cloud. He was looking at another galaxy, though that word hadn’t been coined yet. He was one of the first to glimpse the true scale of the cosmos.

He sketched it with remarkable accuracy, and that image would haunt astronomers for decades. Were these “spiral nebulae” part of the Milky Way? Or were they distant “island universes”?

We wouldn’t know the answer until the 1920s—but the question started with the Leviathan.

Decline and Resurrection

Eventually, the Leviathan fell into disuse. Weather, corrosion, and the telescope’s awkward handling made it less practical over time. By the early 1900s, it was dismantled. The original mirror and tube were stored or scrapped. It became a memory.

But not forever.

In the 1990s, a team of historians, engineers, and astronomers in Ireland rebuilt the Leviathan. Today, you can visit it at Birr Castle, where it stands once again, towering between its original stone walls as a monument to scientific ambition.

Legacy

The Leviathan of Parsonstown wasn’t just a bigger telescope. It was the first great eye powerful enough to suggest that the universe was not just the Milky Way. It hinted at a universe of galaxies, structures, and distances beyond imagination.

It was born of curiosity, not necessity. Built not by a professional observatory, but by a man in rural Ireland who refused to accept the limits of the sky. And it proved that sometimes, the only way to see the universe more clearly is to think absurdly big.

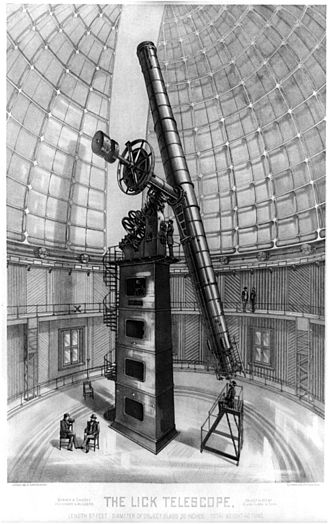

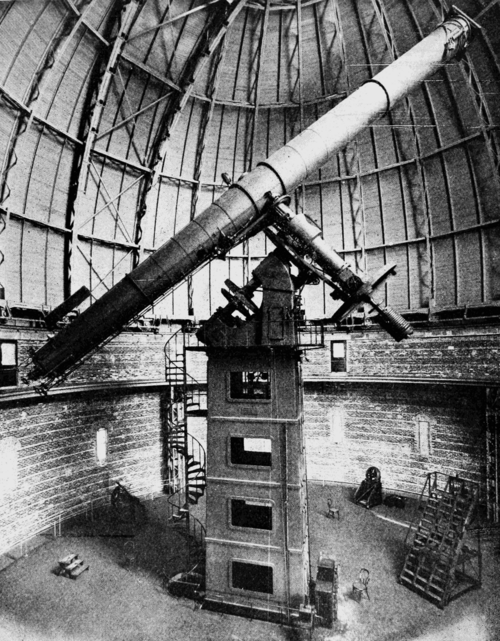

7. Lick Observatory (1888)

Pioneer of American Astronomy

Location: Mount Hamilton, California, outside San Jose

Type: Refractor (36-inch lens)

Claim to Fame: The largest refractor before Yerkes. Discovery of Amalthea, the fifth moon of Jupiter.

Perched high above San Jose on the summit of Mount Hamilton, Lick Observatory is more than just a historic site. It’s a landmark in the story of modern astronomy. Completed in 1888, it was the world’s first permanent mountaintop observatory and home to the most powerful telescope of its time. Its construction marked a shift in astronomical science, turning observation into a high-altitude, precision-driven enterprise that would influence research institutions for decades.

A Monument to Vision—and a Visionary

Lick Observatory owes its existence to an eccentric and ambitious man: James Lick, a real estate mogul and the richest man in California in the mid-1800s. Near the end of his life, Lick decided he wanted to leave behind a legacy, something grand and enduring.

Scientific Firsts and Lasting Contributions

Over the years, Lick Observatory became a powerhouse of astronomical research. Some of its milestones include:

- 1892: Discovery of Amalthea, the fifth moon of Jupiter, by E.E. Barnard—the first planetary moon discovered with a telescope since Galileo.

- 20th Century: Pioneered stellar spectroscopy and radial velocity studies, helping lay the groundwork for understanding stellar motion and exoplanet detection.

- Supernova research: Astronomers at Lick Observatory helped classify and understand the types of supernovae, which is crucial for measuring cosmic distances.

“Even the habitually frivolous become thoughtful when they enter the presence of the great telescope.” — noted by James Edward Keeler, early Lick Observatory director, in an article for The Engineer in 1888

A Working Observatory in the Modern Era

Today, Lick is operated by the University of California and continues to conduct research. Despite growing light pollution from Silicon Valley, adaptive optics and new instruments keep Lick relevant in 21st-century science. It’s also a training ground for young astronomers and a public outreach hub, offering tours, talks, and telescope viewing nights.

Legacy

Lick Observatory was the first to prove that science belongs on mountaintops, where clearer skies offer a window into the universe. It paved the way for later giants, such as Mount Wilson, Palomar, and the Keck Observatory. And it all started with a grand vision and a 36-inch lens on a lonely California peak.

All these years later, it still stands, watching the stars and preserving the legacy of James Lick.

8. Yerkes Refractor (1897)

The Last Giant of Glass

Location: Williams Bay, Wisconsin, USA

Type: Refractor (40-inch lens)

Claim to Fame: Largest refracting telescope ever built

Public Domain

On the shore of Geneva Lake in Wisconsin stands a monument marking a pivotal moment in astronomy. Opened in 1897, the Yerkes Observatory is home to the largest refracting telescope ever built. It’s a 40-inch lens crafted from pure optical glass, making it a mechanical masterpiece and a scientific landmark.

The Yerkes Telescope marked the final chapter in the era of refractors and served as the launchpad for modern astrophysics. In a very real way, it bridged the age of stargazers and the era of cosmologists.

The Vision of a Telescope Empire

The man behind Yerkes Observatory was George Ellery Hale, a driven and visionary astronomer who, at the age of 29, persuaded the University of Chicago and railroad tycoon Charles T. Yerkes to fund his dream.

At the time, refracting telescopes (which use lenses instead of mirrors) were the gold standard. The world’s largest was the 36-inch at Lick Observatory in California. Hale wanted bigger. He sought the most powerful telescope on Earth and aimed to establish a world-class research center around it.

What It Discovered

While its lens wasn’t as light-gathering as the big reflectors that would follow, the Yerkes Telescope was mighty for its time. It played a key role in early spectroscopy, stellar photography, and the birth of modern astrophysics.

Some of its key contributions:

- Mapping binary stars and stellar motion with incredible precision

- Spectral analysis of stars and nebulae

- Observations of planetary detail unmatched by any other telescope of the era

It also played a foundational role in training astronomers who would shape the 20th century, including Edwin Hubble, who worked there before his legendary tenure at Mount Wilson.

Decline and Revival

By the late 20th century, Yerkes had faded from the forefront of scientific research. In 2018, the University of Chicago closed it—but not for long.

Thanks to a public-private partnership and intense local support, the observatory was reopened in 2022 as the Yerkes Observatory, now known as the Yerkes Future Foundation. Today, it’s undergoing restoration and rebirth as a center for science education, history, and outreach.

Legacy

The Yerkes Telescope stands as the pinnacle of refracting telescope technology. Never surpassed, never forgotten. It helped lay the groundwork for how we observe the sky, train scientists, and turn stargazing into science. It’s not just a relic. It’s a reminder that bold ideas, backed by precision and passion, can outlast the trends of technology and still inspire new generations to look up.

9. The Hooker Telescope (1917)

The 100-Inch Mirror That Changed Everything

Location: Mount Wilson Observatory, California, USA

Type: Reflector (100-inch mirror)

Claim to Fame: Proved the universe is expanding

High above Los Angeles, perched on the chilly summit of Mount Wilson, stands a telescope that cracked open the cosmos. Built in 1917, the Hooker Telescope was the most powerful optical telescope on Earth for decades. However, its true legacy lies not just in its size, but in what it revealed: that the universe is much larger and far stranger than anyone had ever dared to imagine.

Building a Giant

In the early 1900s, astronomer George Ellery Hale was fixated on creating larger telescopes. After successfully constructing a 60-inch reflector on Mount Wilson, he immediately began planning a more ambitious project: a 100-inch reflecting telescope. This telescope was named after John D. Hooker, a Los Angeles businessman who contributed partial funding for its development.

The telescope was constructed during a turbulent time, interrupted by funding issues, technical delays, and the outbreak of World War I. But after a decade of struggle, the Hooker Telescope saw “first light” on November 1, 1917, with Jupiter being the first target.

The Discoveries That Redefined the Universe

Shortly after it was operational, the Hooker Telescope became the frontline tool for unraveling cosmic mysteries. It was here that Edwin Hubble, a young astronomer from Missouri with a law degree and a boxer’s chin, would forever alter our understanding of space.

1. The Universe Has Galaxies

At the time, many astronomers believed the Milky Way was the entire universe. Fuzzy patches in the sky, known as “spiral nebulae,” were assumed to be nearby clouds of gas.

Hubble spent many long, frigid nights at the eyepiece of the Hooker telescope, carefully tracking stars by hand through mechanical controls. He often remained at the instrument for up to eight hours at a time, manually keeping stars centered in the crosshairs via a paddle-and-gear mount, before modern automation took over.

Most notably, he used the Hooker Telescope to observe Cepheid variable stars in the Andromeda “nebula.” These stars had a known brightness relationship, which allowed him to calculate Andromeda’s distance.

The result: Andromeda was far outside the Milky Way. It wasn’t a gas cloud—it was a galaxy, like ours. This discovery in the early 1920s expanded the known universe by millions of light-years.

I’m grateful that backyard astronomers like myself have telescopes to enjoy a great view of Andromeda, similar to what Hubble captured so many years ago.

2. The Universe is Expanding

But Hubble wasn’t done.

In 1929, working with Milton Humason, he used redshift measurements of galaxies, combined with distance estimates, to discover a stunning pattern: the farther away a galaxy is, the faster it’s moving away from us. This became Hubble’s Law and the first direct evidence that the universe is expanding.

10. The Hale Telescope (1948)

200-Inch Eye That Opened the Deep Universe

Location: Palomar Observatory, California, USA

Type: Reflector (200-inch mirror)

Claim to Fame: Most powerful optical telescope of the mid-20th century

On a mountain peak above Southern California, a machine of glass and steel began watching the stars in 1949. It wasn’t just big. It was revolutionary. And its 200-inch reflector perched on Palomar Mountain redefined the boundaries of the known universe.

The Dream of George Ellery Hale

The Hale Telescope is named after George Ellery Hale, the astronomer who made big telescopes his life’s mission. He helped build the world’s largest telescopes three times already: the 40-inch refractor at Yerkes, and the 60-inch and 100-inch reflectors on Mount Wilson.

But Hale wanted more—a telescope big enough to see to the edge of the universe.

“Like buried treasures, the outposts of the Universe have beckoned to the adventurous from immemorial times. … Each expedition into remoter space has made new discoveries and brought back permanent additions to our knowledge of the heavens.” — from Hale’s 1928 Harper’s Magazine article and subsequent Rockefeller Foundation proposal.

In 1928, with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation, the plan for a 200-inch reflecting telescope began. Hale wouldn’t live to see it completed as he died in 1938, but his vision drove the project forward.

An Engineering Marvel

When completed in 1949, the Hale Telescope was the largest optical telescope in the world. Nothing even came close. Its size and technology made it not just bigger, but far more sensitive and stable than anything that came before.

The first object observed during the “first light” of the Hale Telescope (200-inch telescope at Palomar Observatory) was the variable star NGC 2261, also known as Hubble’s Variable Nebula, located in the constellation Monoceros.

This observation took place on January 26, 1949. The telescope was operated by astronomer Edwin Hubble himself, making the event both historically and symbolically significant.

I had the pleasure of visiting the Hale Telescope years ago. A video of my trip is below.

Still Watching the Sky

Although it’s no longer the largest telescope on Earth, the Hale remains active today, maintained and operated by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech). It continues to contribute to cutting-edge science, with its data used in conjunction with space telescopes such as Hubble and the James Webb.

Legacy and Influence

The Hale set the standard for modern astronomy. It inspired a new generation of mountaintop observatories, including the Keck telescopes in Hawaii and the Very Large Telescope in Chile. It also trained generations of astronomers, many of whom would go on to make breakthroughs in cosmology, exoplanet research, and galactic science.

The Hale Telescope was more than just a larger mirror; it represented a vision grounded in the belief that human creativity could extend beyond our galaxy and help us map the entire universe. It revealed that the cosmos is violent, dynamic, and far more expansive than we can imagine. Most importantly, it demonstrated that with the right tools and the right questions, we could begin to understand it.

Sources for the article and for further reading

Galileo Project – Rice University: https://galileo.library.rice.edu/

Galileo: Watcher of the Skies by David Wootton

“Account of a Comet” (1781): Herschel’s original publication where he described his discovery of Uranus (originally thought to be a comet) https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/accountofcomet7121781hers

BBC Sky at Night Magazine on Leviathans Legacy: https://www.skyatnightmagazine.com/space-science/the-leviathans-legacy

Yerkes Observatory: https://yerkesobservatory.org/about/legacy/

Mt. Wilson Observatory: https://www.mtwilson.edu/

Sky & Telescope on Hooker Telescope: https://skyandtelescope.org/astronomy-news/the-star-that-changed-ouruniverse/

Lick Observatory: https://www.ucobservatories.org/observatory/lick-observatory/

Palomar Observatory: https://sites.astro.caltech.edu/palomar/homepage.html

Celebrating Caltech’s Founder and Builder of Large Telescopes: https://www.caltech.edu/about/news/celebrating-caltechs-founder-and-builder-large-telescopes-82669

I must object that you have left out Newton’s reflector. He proved that the main objective didn’t have to be glass and birthed the 2nd evolutionary family line of telescopes that would eventually supersede the 1st line of refractive scopes.

I must also specify that you need a companion article on mountings. They are at least half the story of telescope history as anyone who has ever steadied a hand held scope or binoculars can attest. Magnification of the subject equally magnifies the errors of keeping the object in view!

Thank you!

LikeLike

Hello Joe! Thanks for taking the time to comment. You know, I agree with your objection! I started writing this post with only a few of the bigger telescopes in mind, but by the time I stopped, I realized I had added several others as I kept going. I realize now I skipped over Newton’s reflector—a big miss indeed. I will update this post soon.

I also appreciate your thoughts on mountings and agree wholeheartedly. I appreciate you stopping by. Clear skies.

Wayne

LikeLike