On a crisp autumn night, if you turn your gaze toward the sprawling constellation of Aquarius, one of the brighter points of light you’ll see is Zeta Aquarii. At first glance, it seems like just another star twinkling in the sky.

But peer through a telescope, and a hidden story unfolds: This isn’t a single star at all, but a binary system, two stars locked in a cosmic dance. William Herschel, the celebrated discoverer of Uranus, first noticed its double nature in 1777 and later included it in his 1782 catalog of double stars. A few years later, Christian Mayer recorded the star in 1784, adding to the early chronicles of this celestial pair.

Finding and Resolving the Binary

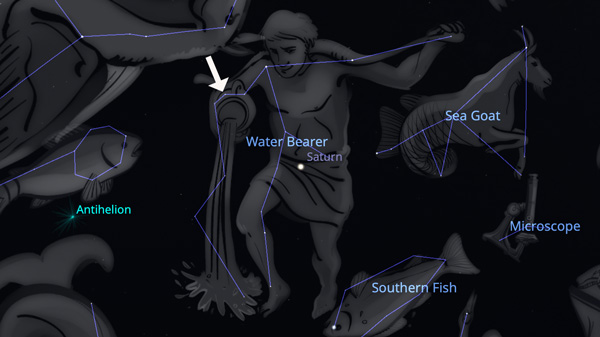

Zeta Aquarii sits about 92 light-years away. Its brightness of a combined magnitude +3.6 makes it visible even in moderately light-polluted areas, though city skyglow can mute this brighter star near the right arm of the water bearer.

For backyard astronomers, splitting Zeta Aquarii into its twin components is a rewarding challenge. Under steady skies, a medium-sized amateur telescope (6–8 inches or more) can begin to separate the pair. They shine nearly equally, making them a striking visual duo rather than a lopsided pairing. See my observation below.

About the Close Pair

Both stars are F-type main-sequence stars. They burn hotter and whiter than our Sun, each with a mass around 1.4 times that of the Sun and radiating roughly three times as much energy. Their similarity makes the system unusual: Many binaries contain mismatched stars of very different sizes or ages, but Zeta’s twins are close in character.

The stars orbit each other with an average separation of about 100 astronomical units (AU), roughly two and a half times the distance from the Sun to Pluto. Their orbit is elliptical, meaning the distance swings wider and closer over centuries.

With a period of about 587 years, humanity has only watched them move through a tiny portion of their cosmic dance. A nice illustration of this orbit is available on the Stelle Doppie website. The website indicates a third, 11th magnitude companion, at only .6 arcseconds away. Also, Andrei Tokovinin provides a 2016 study on this triple star system for those who want to dig deeper.

To the naked eye, of course, it will always look like one steady point, a reminder that the cosmos often hides complexity behind apparent simplicity.

My Observations

| Date | October 8, 2021 |

| Time | 9:30 p.m. |

| Location | Seattle, WA |

| Magnification | 339x |

| Scope | Meade 8″ SCT |

| Eyepiece | 6mm |

| Seeing | Average |

| Transparency | Average |

On this early October night, I train my scope on Aquarius and spot Zeta Aquarii. Through the 12mm eyepiece, it’s just a stretched light yellow point of light. I switch to the 6mm, pumping up the magnification over 300x. The star shivers in the unstable air, but with averted vision, I see the two stars, barely split. A quiet thrill for sure as this has to be one of the tightest binaries I’ve witnessed.

Key Stats

| Constellation | Aquarius |

| Best Viewing | Autumn |

| Visual Magnitude | +4.3 | +4.49 |

| Separation | 2.4″ |

| Position Angle | 152.2° |

| Milky Way Location | Orion Spur |

| My Viewing Grade | B+ |

| Designations | STF 2909, SAO 146108, HIP 110960, GC 31398, HR 8558, Zet1 Aqr, 55 Aquarii, HD 213052, 55 Aqr, ζ1 Aqr |

Sources and Notes

Stelle Doppie. (n.d.). WDS 22288-0001 STF 2909 AB (Zet1 Aqr). Stelle Doppie. Retrieved August 23, 2025, from https://www.stelledoppie.it/index2.php?iddoppia=99875

Tokovinin, A. (2016). The triple system Zeta Aquarii: Based on observations obtained at the Southern Astrophysical Research (SOAR) telescope. The Astrophysical Journal, 831(2), 151. https://doi.org/10.3847/0004-637X/831/2/151

Sketch by Wayne McGraw