Time bends kindly in this square—

Destiny walks slow, so linger there.

Where sunlight marks the hours we share,

And St. John’s bell calls hearts to prayer,

Hope for love… if you dare.

In historic Savannah, the Spanish moss doesn’t just hang beneath old oaks; it drifts in the warm air like slow-moving curtains, stirring as though the city itself is breathing. Cobblestone corridors unfold square by square, each one extending an invitation to wander just a little farther, to pause just a little longer.

Walk south on Habersham Street from the river, and let the midday sun guide your steps. You’ll find the crowds thin, the river breeze steadies, and before long, you arrive at Troup Square.

At its center rises something unexpected for Savannah, a large Armillary Celestial Sphere. And only a stone’s throw away stands a modest church with a history all its own, once home to James Lord Pierpont, who penned the Christmas classic “Jingle Bells.”

The Iron Heavens of Troup Square

What may look like a gyroscope from a distance reveals itself, up close, as a variation of an ancient astronomer’s tool called an armillary sphere.

Long before telescopes or modern observatories, early sky watchers used instruments like this to imagine the heavens as a vast sphere surrounding the Earth. Its circles and angles helped them follow the slow drift of stars and paths of planets, turning the sky into something they could measure and understand.

Reading the Sphere

When I first approached the Troup Square sphere, I thought it was iron. But as I drew closer, sunlight revealed hints of green and blue, a patina that spoke of bronze alloy aged gracefully by Savannah’s sun and rain.

A rod pierces its center, tipped with a star on one end and an arrowhead on the other. This rod, also known as a gnomon, aligns with Earth’s axis, pointing toward the celestial north pole, where Polaris, the North Star, keeps its watch.

When the sun strikes the gnomon, it casts a shadow onto the wide ring, where Roman numerals mark the hours.

Now, sometimes, Savannah’s oaks shade the sun a little too well. If all you see is dappled light across the numerals (as in my photo above), don’t worry. You can still get a sense of how the sphere works.

Walk to the side of the sphere opposite the sun. Check the time on your phone, then stand behind the numeral that matches it and look upward. You’ll notice the sun hovering roughly across from the number on the ring. Even in soft, filtered light, you can see the sphere in action.

Also, while you’re there, be sure to look around the ring at the golden zodiac symbols.

You’ll see Aries the Ram, Taurus the Bull, Gemini the Twins, Cancer the Crab, Leo the Lion, Virgo the Maiden, Libra the Scales, Scorpio the Scorpion, Sagittarius the Archer, Capricorn the Sea Goat, Aquarius the Water Bearer, and Pisces the Fish.

In traditional astronomy, the positions of the Moon, planets, and stars were often described in terms of the zodiac signs. The symbols help users understand which part of the sky a planet or star is located in.

Then look down at the six turtles supporting the sphere. In ancient Eastern stories, the world was believed to rest on the back of a great cosmic turtle.

These turtles echo that idea, linking the heavens above with the ground beneath your feet. And when December comes, they trade their timeless duty for Santa hats and a bit of Savannah cheer!

Chris Parkin with Oxford’s History of Science Museum provides a solid overview of the armillary sphere if you want to learn more about these fascinating devices.

From Polaris to Jingle Bells

The armillary sphere honors the cosmos’s steady design, while the church across Habersham Street feels like its artistic counterpart.

Photo: Wayne McGraw

When I arrived at the sphere, I didn’t know that the Unitarian Universalist Church across the street had its own musical history thanks to a former organist, James Lord Pierpont.

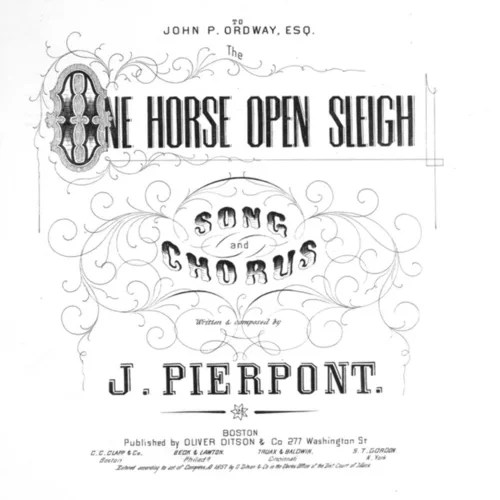

In the fall of 1857, Pierpont arrived in Savannah to serve as the church’s organist and music director, where his brother was the minister. On September 16 of that year, he published the song One Horse Open Sleigh, which would later become known as Jingle Bells. Most scholars believe he had already composed it in Boston, though a long-standing debate continues over whether its true origin lies in Medford, Massachusetts, or Savannah.

At the time, it wasn’t a sensation, and historians have noted its potentially controversial nature, given its original use. The song, thought to have begun as a drinking tune about sleigh races and picking up girls, might have fit better with an 1980s hair-metal band!

And yet, that simple melody eventually jingled its way into history.

Between Stars and Sleigh Bells

In the center of the square stands the sphere, its rings echoing a universe guided by order and motion.

Across the street, the echoes of Jingle Bells remind us of something altogether different: a joyful, human tune about winter and nostalgia.

It feels fitting that this song would be the first ever broadcast from space, when astronauts on Gemini 6 played it on December 16, 1965.

Savannah is a city of contrasts, a place of rich history, ghost stories, and the intrigue of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. Troup Square offers a calm pause, a place to stand between the iron map of the heavens and the human warmth of a song that has traveled from a small church to the far reaches of space.

Sources and Notes

American Music Preservation. (n.d.). Jingle Bells song history. https://www.americanmusicpreservation.com/jinglebellssong.htm

History of Science Museum. (n.d.). Armillary sphere. https://www.hsm.ox.ac.uk/armillary-sphere

Savannah.com. (n.d.). Troup Square. https://www.savannah.com/troup-square/

Visit Savannah. (n.d.). Savannah’s squares and parks. https://visitsavannah.com/article/savannahs-squares-and-parks