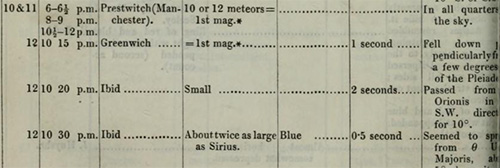

As evening deepened on December 10, 1862, Robert P. Greg stepped out under the cold skies of Prestwich, just outside Manchester, England. Around 6 p.m., quick strokes of light began to flash before him from “all quarters of the sky.”

Thousands of miles away across the restless Atlantic waters, the same heavens stretched overhead. There, Benjamin Marsh in New Jersey and Professor Alexander Twining in Connecticut witnessed the same phenomenon.

Three men found themselves linked beneath the firmament, much like the observers who watched the great Leonid shower 29 years earlier. Instead of the breathtaking display seen decades before, the sky offered these men, and anyone else looking up, only a drizzle of 10 to 12 shooting stars per hour.

While these sightings are the first well-documented reports of the Geminids, earlier accounts suggest the stream may have been observed as far back as 1833, and perhaps much earlier. For a deeper look, W. E. Besley offers a helpful summary beginning on page 366 of The Observatory, volume 23, published in 1900.

A 19th Century Mystery

For more than a century, the source of these winter lights remained a mystery.

It wasn’t until October 11, 1983, 120 years after Robert P. Greg first looked up from Manchester, that the silence was broken at the University of Leicester. There, PhD student Simon F. Green and astronomer John K. Davies were scanning data from the IRAS satellite, hunting for fast-moving objects.

At the time, Green’s supervisor assigned him to develop software for the IRAS Fast Moving Object Survey, which scanned rejected data for fast-moving asteroids. He and John Davies alternated shifts on the project, and Green was on duty when 3200 Phaethon appeared. The two ultimately shared credit for the objects they uncovered, including the asteroid Phaethon.

How We Know Phaethon is Related to the Geminids

Phaethon isn’t a comet; it’s an asteroid—a rock. It behaves like a “rock comet,” shedding debris not through melting ice, but most likely through the violent fracturing of its surface.

In fact, to unravel the origin of the Geminid stream, scientists recently turned to data from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe to test several possible ways the meteors might have formed. They then compared these simulations with observations made from Earth. The results pointed toward a violent beginning. The Geminids most likely sprang from a sudden, powerful event, such as a high-speed collision with another object or a burst of gas from their parent body that sent debris scattering into space.

Regardless of the exact scenario, Phaethon and the Geminids share a common lineage, moving through the solar system as if cut from the same celestial cloth. Each follows an inclined, elongated loop around the Sun—meaning their orbits are stretched into ovals rather than circles, and tilted relative to Earth’s orbital plane.

Then there’s the matter of speed. Geminid meteors strike Earth’s atmosphere at a velocity of around 35 kilometers per second, or 78,000 miles per hour. Only debris coming from Phaethon’s orbit can hit us at exactly that speed. No other known object in the solar system matches it.

The Colors of Stone

Because they are rocky debris rather than the soft dust of comets, Geminid meteors are denser and strike the atmosphere at a slightly slower speed. This gentler plunge allows their light to unfurl more fully across the sky. Also, their metal-rich makeup enables them to burn in a variety of hues, much like fireworks.

According to Joe Rao, about two-thirds of the Geminids streak across the sky in pure white. About a quarter glows golden, while the remainder blaze in a mix of red, orange, blue, and sometimes green! Each color hints at the elements within.

Tips on Watching the Geminids

Look Up: The Geminids appear to fan out from the constellation Gemini, near the bright stars Castor and Pollux. This spot in the sky is called the radiant. But you don’t need to stare directly at it. In fact, you’ll see more if you simply look upward and let your eyes wander. The meteors can flash across any part of the sky!

Find a Dark Spot: Seek out the darkest place you can, away from city lights or suburban glow. The darker the surroundings, the more Geminids you’ll catch.

Get Comfortable: This may be the most important tip of all! After decades of watching meteor showers, I can say that a warm blanket and a reclining chair are the best pieces of equipment you’ll ever bring.

Reflection

The Geminids, or “gems,” are autumn’s last sparks slipping into winter’s dark. They are born of stone rather than ice, and they remind us that even in a torrid fall, friction can create light. In each slash across the sky, we glimpse hope that even the broken can shine.

There’s something profound in knowing the same meteors that brushed those skies in 1862 now glide across ours, linking us to observers long gone and to others we’ll never meet. The world has witnessed much since 6 p.m. on December 10, 1862, when Robert Philips Greg and others recorded the Geminids.

Beneath these falling stars of December, we’re connected to the past, reassured that the future will move forward as well. The firmament remains steadfast, no matter the year or the century.

Sources and Notes

Astronomy Now. (2015, December 12). Astronomers recall discovery of Phaethon — source of Geminid meteors. Astronomy Now. https://astronomynow.com/2015/12/12/astronomers-recall-discovery-of-phaethon-source-of-geminid-meteors/

Cukier, W. Z., & Szalay, J. R. (2023). Formation, structure, and detectability of the Geminids meteoroid stream. The Planetary Science Journal, 4(5), 109. https://doi.org/10.3847/PSJ/acd538

Dobrijevic, D. (2025, December 5). Geminid meteor shower 2025 peaks next week: Here’s what you need to know about this year’s best meteor shower. Space.com. https://www.space.com/stargazing/geminid-meteor-shower-2025-peaks-next-week-heres-what-you-need-to-know-about-this-years-best-meteor-shower

Harbster, J. (2012, December 11). Wishing upon the shooting stars: The Geminid meteor shower. Inside Adams. https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2012/12/wishing-upon-the-shooting-stars-the-geminid-meteor-shower/

Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, 64th Meeting, 1895. Internet Archive. https://archive.org/details/reportofbritisha64brit/page/240/mode/2up.