February 9, 1913

Walter Haight, Parry Sound, Canada

The cold deepened as the hour slipped past nine in Parry Sound, where northern Ontario hardens into rock, forest, and open water. Along the Sound, the last of the pewter light drained away, leaving the sky black and the land frozen.

Walter Haight was finishing his Sunday snowshoe trek when his boots started to slip.

He leaned down to fix the leather toe strap.

“Look,” his friend called out.

Walter straightened. Something entered the sky that did not belong to it—a round, burning presence.

The golden-red orb moved steadily, tracing a low path above the horizon. Walter’s eyes stayed with it.

“Look. There and there!” his friend exclaimed, pointing just behind the tail of the first meteor.

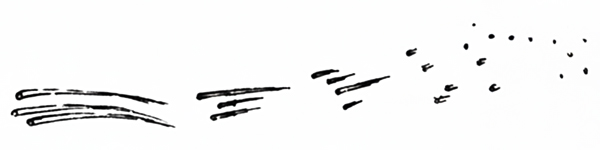

Light after light arrived, evenly spaced.

“It looks like a squadron of torpedoes following a battleship,” Walter thought.

James Bolton, 23 Miles From Toronto, Canada

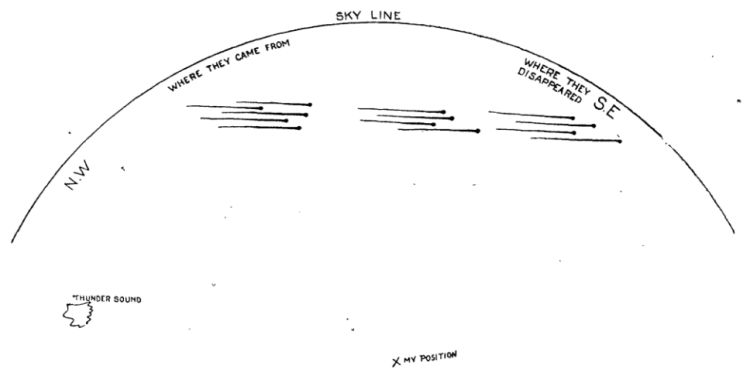

About a hundred miles south, James Bolton checked his watch. The metal felt cold against his thumb. It read 9:05.

A steady light appeared in the northwestern sky and was moving toward him.

He took it at first for an airplane, some early contraption, bolted together, with lamps on it.

But the moving glow didn’t waver until it started shedding sparks and dragging a tail. Others followed it, spaced and orderly. He watched until they vanished a few minutes later.

Afterward, a thunderous clap.

Bolton tried to capture the moment in words: “I have been fortunate enough to see nearly every big meteoric display for the past 50 years, but never saw anything as fine as this.”

Miss Catharine Duncan, Thamesville, Canada

Nearly three hundred miles south of Parry Sound, in Thamesville, the sky was about to do the same strange thing.

Miss Duncan stood outside with her brother. The sky was a “misty dark,” as she would later say.

“Look—an airship,” her brother called, pointing toward the constellation Cassiopeia.

A bright star emerged and moved steadily southeast, growing more luminous as it crossed the sky.

“Mrs. M’s chimney is on fire!”

Miss Duncan turned toward the house, though a wall of spruce trees some seventy feet away blocked her view. The smaller lights trailing the brilliant star spat and scattered like sparks. For a moment, she mistook the falling meteors for embers bursting from the hidden chimney beyond the trees.

She and her brother crossed the street to keep the procession in view, remarking that it looked like a dozen fish swimming at intervals, one after another. The last lights lingered faintly like wisps of luminous gas.

Colonel W. R. Winter, Waterville, Bermuda

Thousands of miles south, in the softer evening air of Bermuda, Colonel W. R. Winter watched a great violet light move across the sky. It came on broad and unbroken, then began to come apart, shedding embers as it travelled.

Smaller fragments followed in yellow and red, like burning paper caught in the wind. Egg-shaped, smaller lights followed the leading meteor.

Off the Coast of Brazil

Farther south, off Brazil’s coast, the clock turned midnight on the ship SS Newlands. Relieved of duty, first mate W. W. Waddell turned toward his bunk. On his way, a bright flare skimmed the horizon, tossing sparks like a rocket.

He yelled out to his second mate to get his attention when “a whole shower of stars of the same kind came shooting across in the wake of the first one.” Upon reflecting on the night, he wrote, “The sight will ever be remembered by those who saw it.”

The Sound of Silence

In Hespeler, Canada, William Foster watched a line of silent lights sail across the sky for three minutes and forty seconds before they vanished. The sky stayed dark for nearly a minute. Then came a rumble of thunder as from a distant storm.

Not far from Foster’s location, Mrs. D. Tighe counted the armada of light as it moved.

“Twenty groups,” she said.

Then a sharp thunder sounded, and another followed.

A man nearby, who was inside at the time, saw nothing. Instead, he heard a heavy rumble that shook his windows like a heavy wagon going down the road.

Some people stood under the lights and heard nothing. Others felt the ground move.

The Mystery

From northern Canada to the South Atlantic near Brazil, witnesses agreed on what they saw. But what were these rank-and-file balls of flame? They skimmed the atmosphere but didn’t burn out like normal shooting stars.

In 2018, Martin Beech and Mark Comte published a paper that finally offered a coherent model for this remarkable event. They propose that Earth had likely captured a small asteroid—perhaps 3 to 4 meters wide—weeks or months earlier. Once snared by Earth’s gravity, this minimoon orbited close. At its nearest, it dipped to within about 200,000 kilometers. That’s roughly half the distance to the Moon, which is 384,400 kilometers away.

At this point, due to gravity’s pull, clusters of rock peeled away, spreading along a vast orbital arc some 15,000 kilometers long.

Then, on that fateful day, Earth moved through this long line of fragments. Instead of entering the atmosphere all at once, they arrived one by one, like beads on a string, at a shallow angle.

These were not the frantic dashes of ordinary meteors, which tear through the sky in violent haste. These crept across the heavens at a deliberate twelve kilometers per second (fairly slow for meteors), skimming the atmosphere in a long, slow burn. And just like rocks skipping on water, some skipped away back into space while others burned up entirely.

Great Meteor Processions

Beech and Comte estimate that events like this occur only every 70-100 years. And history seems to back up this assertion. We know of other occurrences, such as the Great Meteor of August 1783.

Then, on July 20, 1860, another meteor procession graced the skies, capturing the attention of Walt Whitman. In his poem “Year of Meteors (1859-60),” he captures the memorable event in a stanza:

“Nor the strange huge meteor procession, dazzling and clear, shooting

over our heads,

(A moment, a moment long, it sail’d its balls of unearthly light over

our heads,

Then departed, dropt in the night, and was gone)“

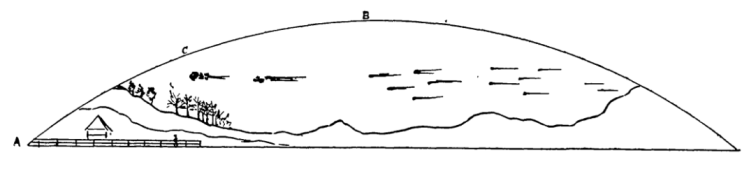

American painter Frederic Church also beautifully illustrated the spectacle. He was on his honeymoon at a small farm he owned outside Hudson, New York. At 9:50 p.m., he stepped outside and watched a line of meteoritic fireballs slide horizontally across the sky. They took roughly half a minute to traverse the darkness, moving from the Great Lakes, over New York State, and onward toward the Atlantic.

Perhaps another procession is forming somewhere as I write this. When Earth next grazes that line of ancient stone, I hope it is night, and that I am looking up in time to see a new chain of sparkling pearls.

There is beauty, I believe, in the miraculous and unplanned. May the next one arrive with no roar, no warning—just a pageant across the sky, leaving us with nothing but wonder.

Sources and Notes

I want to acknowledge the fine essay by Horace A. Smith, which helped build out the narrative of this article.

Banner photo: Hahn, G. (ca. 1913). Meteoric display of February 9, 1913, as seen near High Park [Painting]. Wikimedia Commons. In the public domain for Canada and the United States. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gustav_Hahn_-_1913_Great_Meteor_Procession.jpg

Beech, M., & Comte, M. (2018). The Chant Meteor Procession of 1913 – Towards a descriptive model. American Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 6(2), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajaa.20180602.11

Chant, C. A. (1913). An extraordinary meteoric display. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, 7(3), 145–213. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015076263337&seq=357

Oates, D. (n.d.). “Year of Meteors (1859–60)” (1865). In The Walt Whitman Archive (M. Cohen, E. Folsom, & K. M. Price, Eds.). The Walt Whitman Archive. https://whitmanarchive.org/item/encyclopedia_entry750

Palmer, D. (2020, January 30). The Great Meteorite of July 1860 – When stars fell to Earth. Geological Collections Group Blog. https://geocollnews.wordpress.com/2020/01/30/the-great-meteorite-of-july-1860-when-stars-fell-to-earth/

RedOrbit. (2018, May 4). Great Meteor Procession of 1913 range uncovered. https://www.redorbit.com/news/space/1112769773/great-meteor-procession-1913-range-uncovered-012413/

Smith, H. A. (2012, June 12). The Great Meteor Procession of February 9, 1913, or the Parade of Saint Cyril. Michigan State University Department of Physics and Astronomy. https://web.pa.msu.edu/people/smith/feb1913.pdf