“One of the most beautiful objects that I have ever seen.”

English astronomer William Henry Smyth.

The sun rested low over Florence. Gold spilled across terracotta roofs, and shadows stretched across streets. Voices drifted from open doorways. The warm evening air smelled of sun-baked stone and the faint sweetness of citrus from hidden gardens. Lanterns began to ignite along stone walls where pigeons stirred.

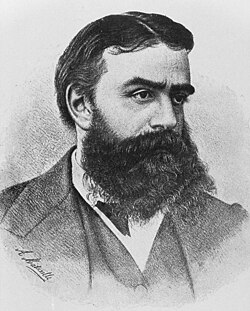

Giovanni Battista Donati climbed the worn steps of his observatory and settled behind the brass tube of his telescope. Night after night, he had done this. Charting. Measuring. Searching. At thirty-two, Donati had surrendered himself to the relentless discipline of observation.

Public Domain

The constellation Leo loomed high as Donati guided the telescope to that familiar patch of sky. At 10 p.m., he noticed something new—a faint blur, barely one-twentieth the diameter of the moon, near the lion’s brow. Easy to miss. Easy to dismiss.

He reached for his logbook to record his observation, unaware that this haze would soon make news across continents:

“I observed a comet which may be new. Estimated position: June 2 at 10 o’clock; RA = 141° 9′, Dec. = +23° 55′. The comet is very faint.”

Summer of Watchful Waiting

Evenings passed, and the pale smudge drifted. Word began to ripple outward from Florence to Berlin, Paris to Greenwich. Through July, the comet remained a prisoner of glass lenses.

By early August, its light grew. Keen-eyed observers in Italy and France reported it edging toward naked-eye visibility. Telegraph wires—the iron threads stitching continent to continent—hummed with news of the approaching visitor.

In a later communication, Donati added:

“On June 2, when I discovered this comet, it appeared as a small nebulosity about 3′ in diameter, with light equally intense across its whole extent. This appearance remained the same until August, during which time the comet developed a noticeable condensation of light at its center—though it could not, however, be called a nucleus.”

Mid-August arrived. Around the 19th, the comet crossed the threshold. No longer confined to brass tubes, it greeted the unaided eye as a subtle glow low in the western sky after sunset. A hint of a stubby tail appeared, but nothing spectacular. In London, Paris, and Boston, editors began printing notices and predictions of splendor to come.

The Arrival of Autumn and Wonder

The comet raced sunward, brightening each night to a level close to that of Saturn. By mid-September, its tail stretched twenty degrees across the sky. That’s roughly the span of a hand at arm’s length with fingers spread! It drifted through Ursa Major, just south of the Big Dipper’s bowl.

Public Domain

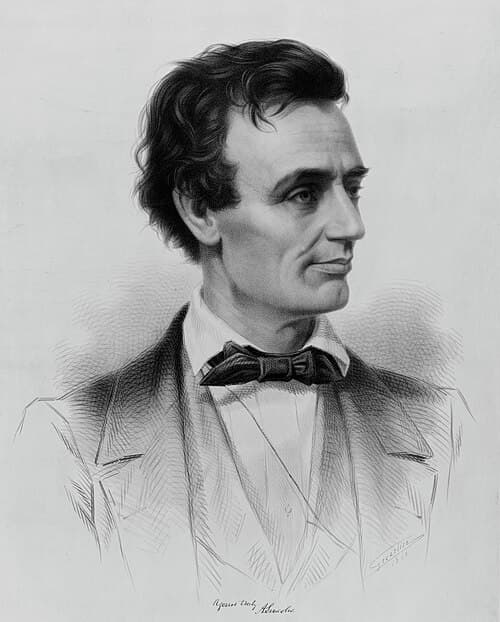

Across the Atlantic, in Jonesboro, Illinois, a lawyer named Abraham Lincoln sat on his hotel porch on September 14th. Tomorrow, he would face Stephen Douglas in their third great debate. The stakes could hardly have been higher. The debate had repercussions far beyond a senatorial seat—it addressed the problem that had divided the nation into two hostile camps and threatened the Union’s continued existence.

Yet tonight, in the gathering darkness, Lincoln spent an hour gazing heavenward at Donati’s Comet.

Perhaps he recalled the breathtaking 1833 Leonid Meteor Shower when the stars fell like snow. He witnessed that heavenly display twenty-five years earlier as a young man. While others panicked, Lincoln had looked beyond the falling stars to see the constellations fixed in their places.

Now with the comet blazing overhead and the weight of the debate pressing upon him, Lincoln probably found the same reassurance. The heavens endured. Truth remained constant. And somewhere beyond the turmoil of earthly politics, the eternal constellations held their course.

First Photographs

Weeks later, the comet would enter history in a new way as the first comet ever photographed. On September 27, 1858, English photographer William Usherwood aimed his camera skyward and captured the celestial visitor, though, sadly, that photograph no longer survives.

The following night, George Bond at the Harvard College Observatory captured his own image through the college’s refractor. Working with glass plates, he experimented carefully. On his first two attempts, he exposed the plates for one to two minutes. For the third, he lengthened the exposure to six minutes, penciling beside it, “think this took”—and it did.

While Bond preserved the comet on glass in Cambridge, observers far beyond the city witnessed the display in their own ways. On that same day, war correspondent Sir William Russell wrote a vivid account from a camp in the Himachal Hills in India.

“At night, as we sat at dinner in our tent, there arose, right above the black outline of the forest, cast into the shade by the clear moonlight, a bright and wonderful star, which, as it ascended, displayed a tail of a faint rose-coloured hue streaming after it.”

The Glory of Early October

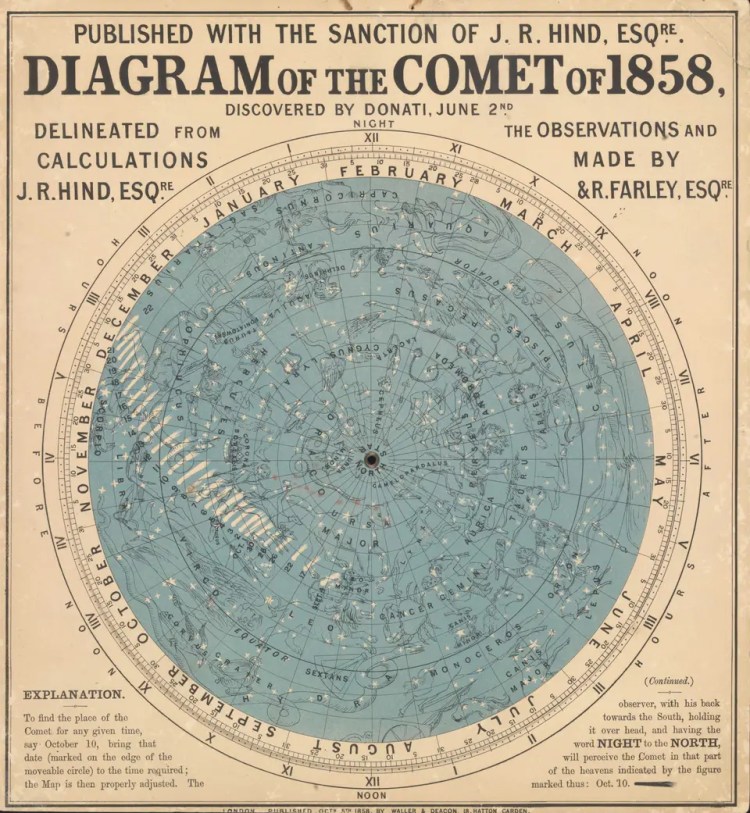

As September surrendered to October, astronomers announced that the comet would pass near Arcturus on October 5th.

Public Domain

In the fading western sky, the comet lifted, and there beside it burned the golden star. For a few rare hours, two diamonds hung in the heavens. Arcturus seemed to rest against the comet’s flowing tail, as though fastened to its banner of light.

Observers watched on. Would Arcturus fade as the comet’s tail swept past? It did not. Its yellow radiance pierced the gauzy veil, a reassuring anchor in the sky.

Across continents and cultures, the comet roused both awe and reflection. Painter William Turner captured the evening in watercolor, inscribing it: “Near Oxford, half past 7 o’clock, P.M. October 5th 1858.”

Thousands of miles away from Turner, Alfred Russel Wallace observed from Tidore, one of the Maluku Islands in eastern Indonesia.

“The nucleus presented to the naked eye a distinct disc of brilliant white light, from which the tail rose at an angle of about thirty degrees with the horizon, curving slightly downwards, and terminating in a broad brush of faint light.”

By October 10th, the comet reached its closest approach—about thirty-three million miles from Earth. So near was it that observers could trace its motion against the stars hour by hour. Its tail now stretched sixty degrees as a luminous arc across the autumn sky.

That evening, British Civil Officer George Elsmie wrote what he was seeing from India.

“We drove for six miles, where horses met us, and then we cantered to the Ganges, crossed in a boat just as the stars had come out. The scene was most lovely; we were silently crossing the river, which was as smooth as glass, and in the west was to be seen the most beautiful celestial trio I ever beheld; rather high up in the sky a gorgeous comet seemed to be diving down like a falling rocket with a magnificent tail of light; on the horizon the new moon, tinged with red from the last beam of the sun, was about to set, and a little to the left, about as high as the comet, Venus was shining in all the glory of her silvery light. It was a truly gorgeous sight.”

Also moved was Reverend Alexander D’Orsey, an English clergyman and Cambridge scholar. So captivated was he by the comet’s brilliance that he penned a poetic tribute:

“Then came the climax! Oh that glorious hour!

The mighty Comet in its pride of power!

No sight like that had ever met my gaze!

No sight like that will living man amaze!

Beautiful vision! Feathery, graceful, bright,

A starry diamond in a veil of light!”

Comet Donati Fades Away

For one hundred and twelve days, the comet remained visible to the naked eye. By mid-November, observers noted that the tail faded. By December, the sweeping arc was reduced to a faint trace, barely discernible through field glasses.

Observers at the Cape of Good Hope Observatory in South Africa made the final observation on March 4, 1859. After that, it was gone.

Giovanni Donati continued his scientific and civic work after that golden summer of 1858, when the comet first appeared above Florence’s terracotta roofs. In 1873, at just forty-six, he was struck down by cholera—a life ended too soon, though full of discovery.

The comet he first glimpsed carried on, a long-period traveler unseen by human eyes for millennia and destined not to return until around 3600. Though Donati’s Comet has vanished from view, it journeys onward through the vastness of space. Gone for now, but not gone forever, it waits for the day it will sweep the heavens once more.

Sources and Notes

Bond, G. P. (1862). Account of the Great Comet of 1858. United Kingdom: Welch, Bigelow, and Company. Available online.

Hale, A. (2020, October 3). Comet of the Week: Donati 1858 VI. RocketSTEM. https://www.rocketstem.org/2020/10/03/ice-and-stone-comet-of-week-41/

Kapoor, R. (2021). Comet tales from India: Donati’s Comet of 1858 (C/1858 L1 Donati). Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1440-2807.2021.01.06

Proctor, M. (1909). The romance of comets. G. P. Putnam’s Sons.

Royal Museums Greenwich. (n.d.). Diagram of the Comet of 1858 discovered by Donati, June 2nd [Object record]. Royal Museums Greenwich Collections. https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-242198

The Lincoln-Douglas Debates: Jonesboro, Union County – September 15, 1858. (n.d.). Mr. Lincoln and Freedom. https://www.mrlincolnandfreedom.org/pre-civil-war/the-lincoln-douglas-debates/jonesboro-union-county-september-15-1858/